The light you keep

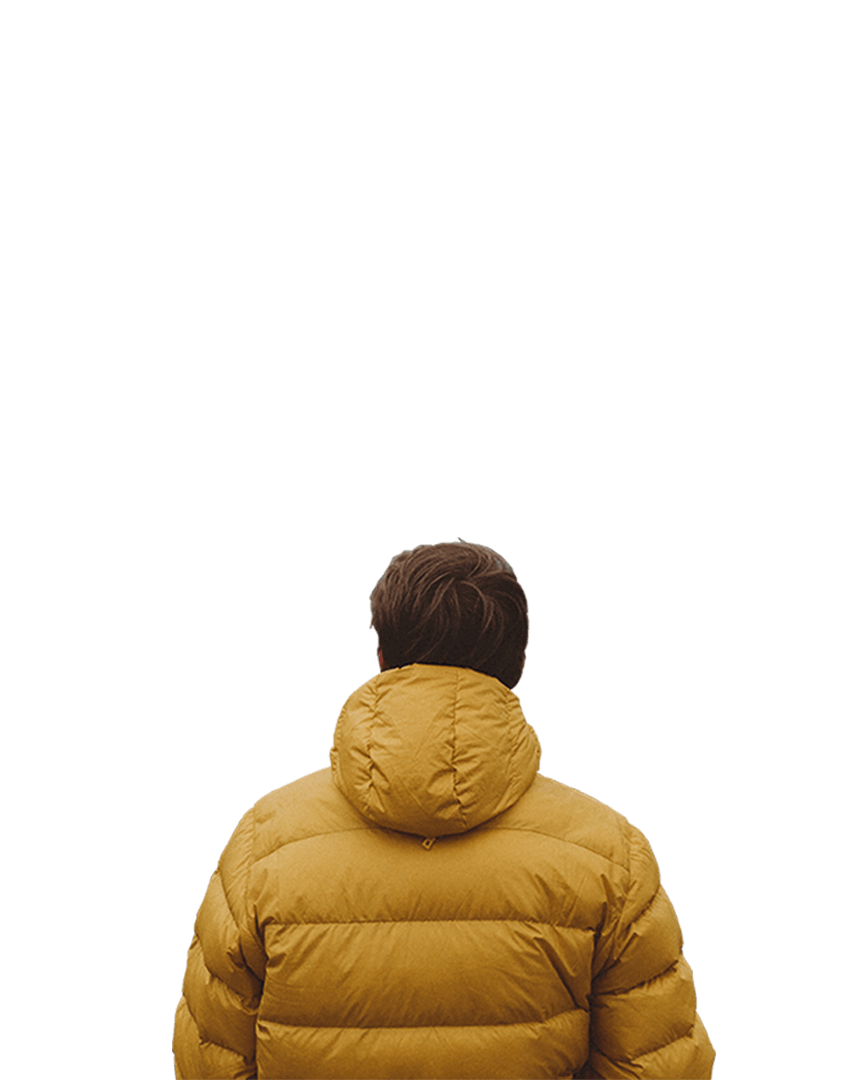

Ernest DeRaps &The Lighthouses of Maine

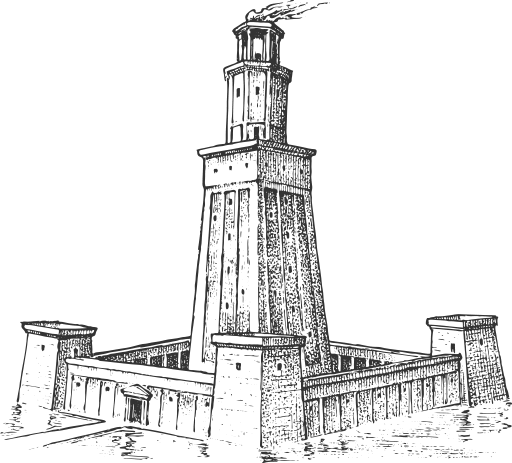

The world’s first great lighthouse was built on the Mediterranean coast of Egypt in the third century B.C., during the reigns of Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II. The Lighthouse of Alexandria stood more than 100 meters high. Its source of light? A huge bonfire blazing atop the tower. It would become known as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

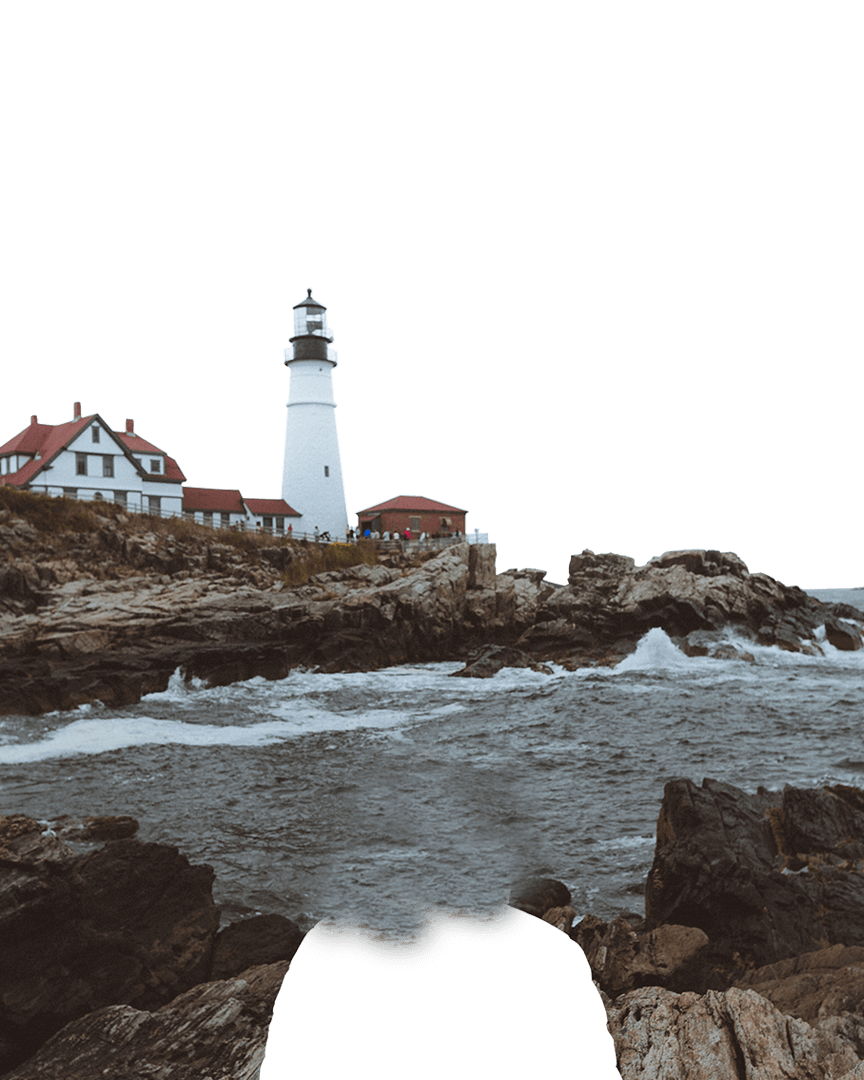

Why are we telling you this? Because two millennia and three centuries later, the Atlantic coast of Maine is home to a lighthouse wonder of the modern world. Not quite as tall, but every foot-candle as inspiring. His name is Ernest DeRaps, “Ernie” to those who’ve made his acquaintance. We would all do ourselves a monumental favor to become one of those people.

“I do everything in earnest,” he jokes. Truer words would be hard to find, even with one of Ernie’s beloved beacons lighting the way.

There are 65 historic lighthouses on the coast of Maine, the oldest dating back to 1787 and built under the direction of a gentleman named George Washington. Every bit the gentleman himself, Ernie dates back to 1928. A little north of 90 years old now, he still lights up a room with the twinkle in his eyes and the smile on his face.

As the youngest of 14 children who grew up in Palmyra in central Maine, Ernie learned the values of hard work, personal responsibility, a sense of duty and knowing how to make the most of your available living space.

In 1946, Ernie joined the Navy and was stationed in San Diego where he quickly displayed a knack for aerial photography. When Ernie’s hitch was over, he refocused his lens on his home base of Maine and eventually joined the Coast Guard. That’s when the offer that would reset the course of his life came in.

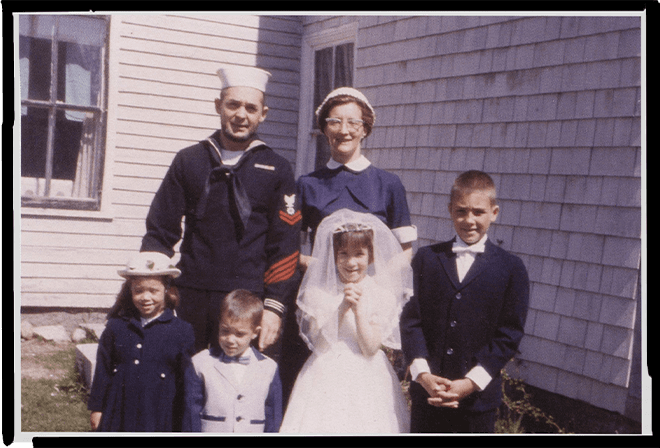

Before he could give his answer, there was one little question. Already with a two-year-old son, his wife, Polly, was four months pregnant with their future daughter. Given the timing, Ernie wasted none and asked her: “How would you like to live in a lighthouse?”

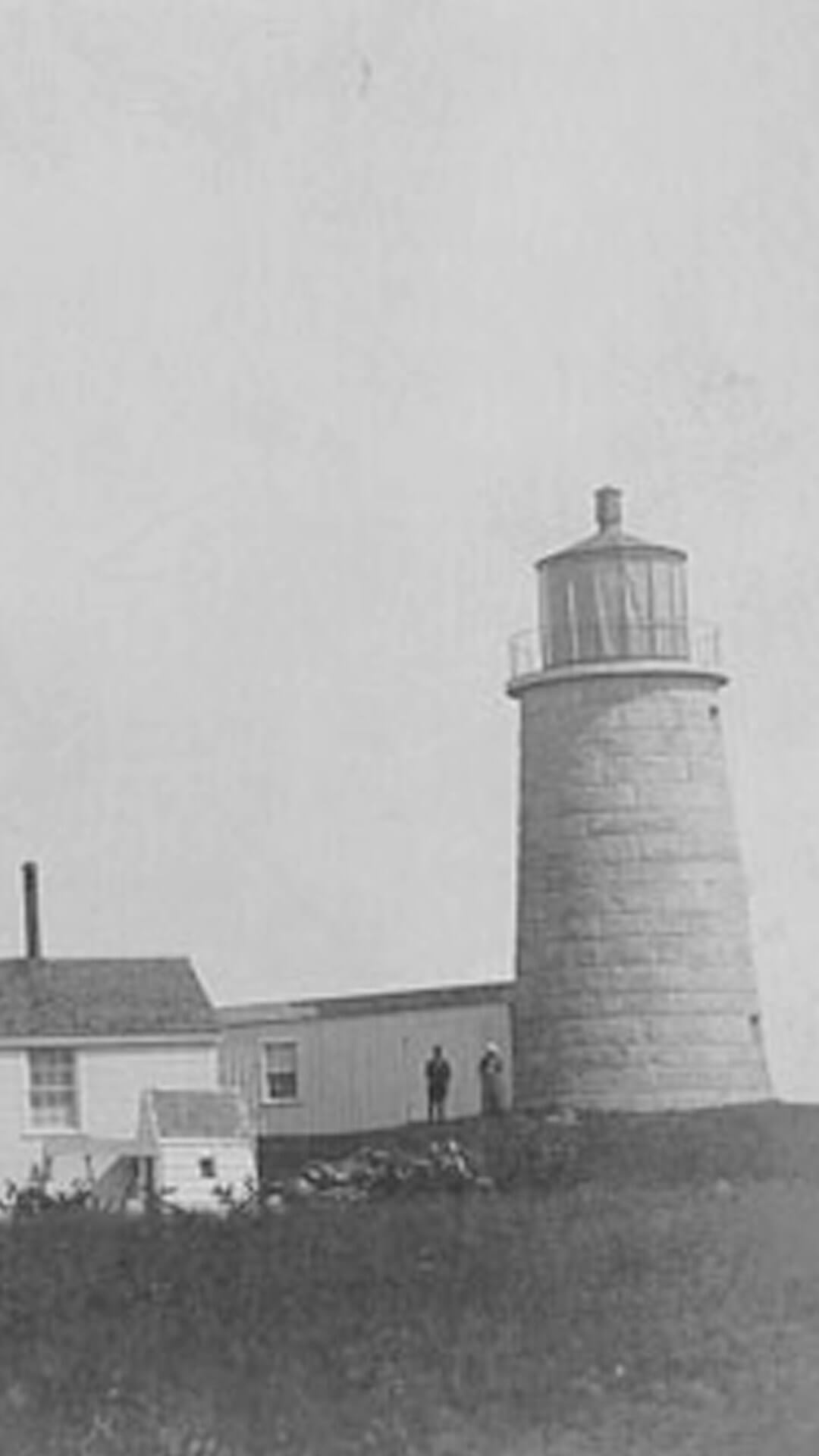

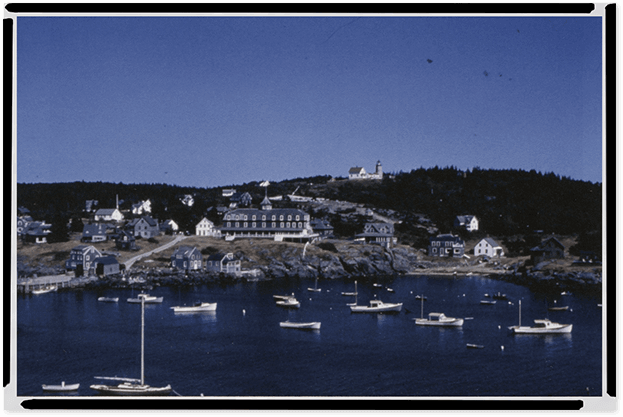

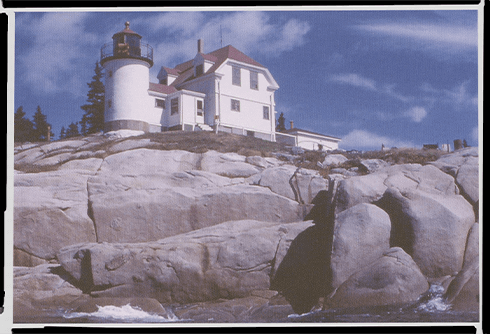

When Polly inquired where, Ernie gave the coordinates: “It’s on an island ten miles off the coast.” A discussion about the compatibility of a pregnancy and a home surrounded by ocean ensued. With a ferry service as plan A and the United States Coast Guard plan B, the Monhegan Island Light would be the first chapter in the DeRaps’ lighthouse story.

Ernie’s wife had just one more question before they carried their son and their belongings over the threshold at Monhegan Island: “What is a lighthouse keeper supposed to do?” During the next several years, she and Ernie would compile the answer.

The first thing Ernie wants everyone to understand is that his primary focus was always the same. To be ever watchful and mindful that there were people out there at sea counting on him, people with lives and loves and families to get home to. It was his job, his responsibility to help them find safe harbor.

The routine Ernie settled into would, over time, prove anything but. And while it might be a stretch to say the Monhegan Island lighthouse had a temperamental personality, it was definitely high maintenance. “I had to have the light lit a half hour before sunset and it had to stay on at least a half hour after sunrise,” Ernie recalls.

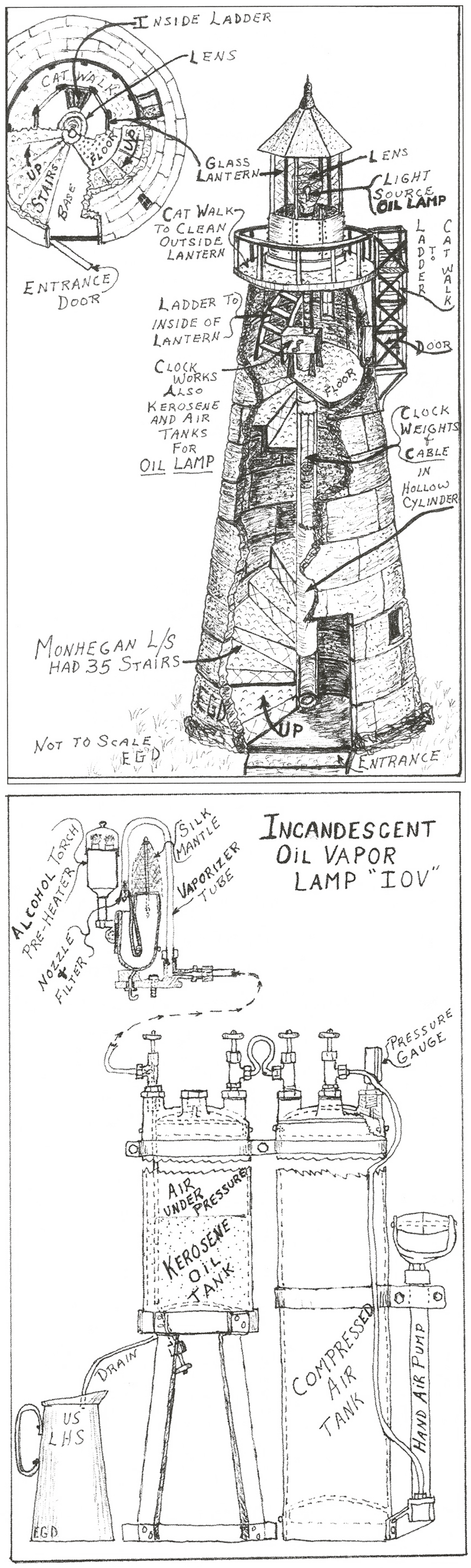

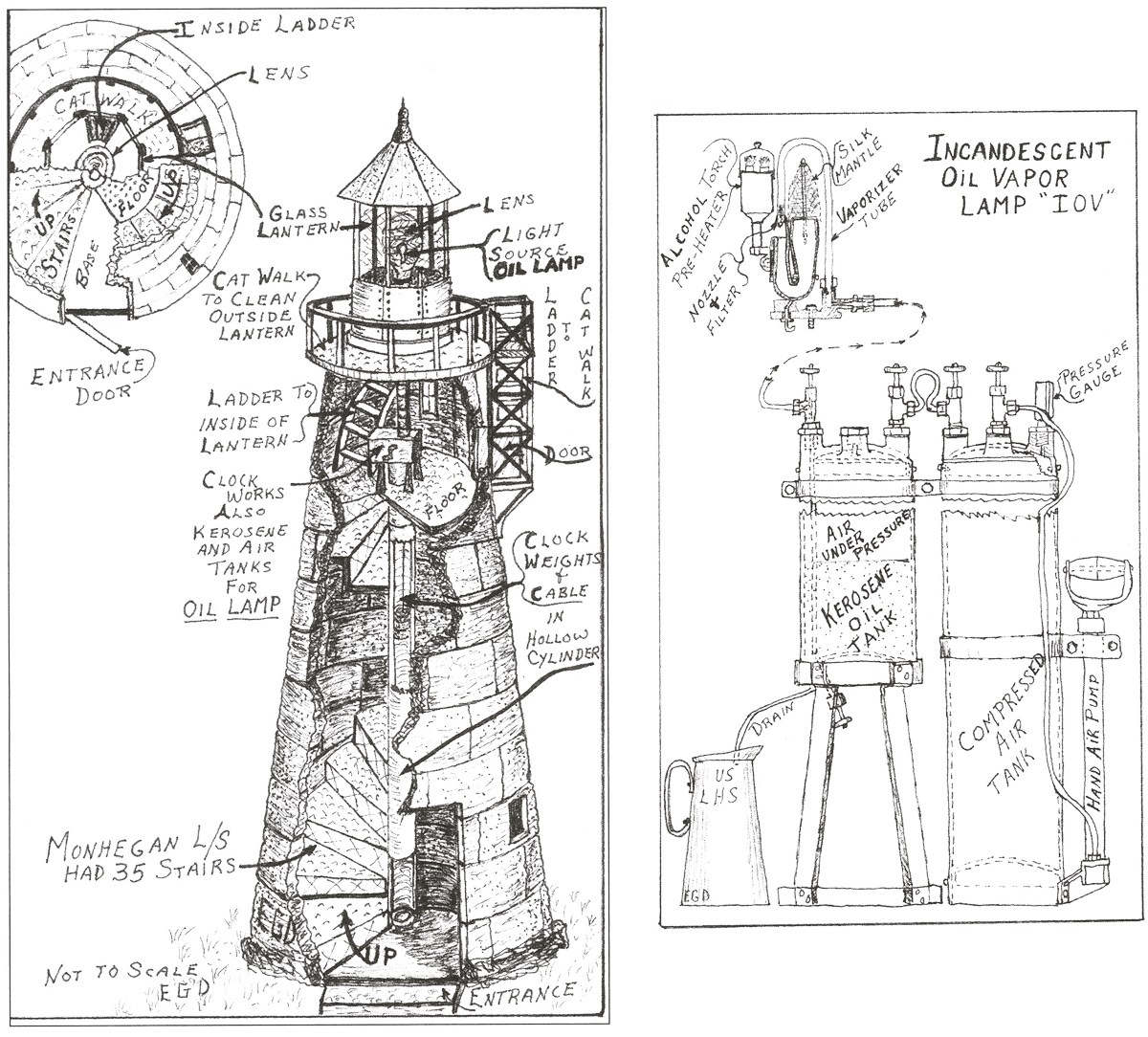

Getting that big old lantern lit and beaming out to sea required more than just the flip of a switch. A whole lot more.

As Ernie describes it:

And it wasn’t just doing it one time for a YouTube video. It was every day, 365 days a year. As Ernie's family grew, and as they moved to other lighthouses on the coast, some days were more eventful than others. Following his stint at the Monhegan Island Light, Ernie, Polly and company would live at two additional lighthouses, Fort Point Light and Brown’s Head Light.

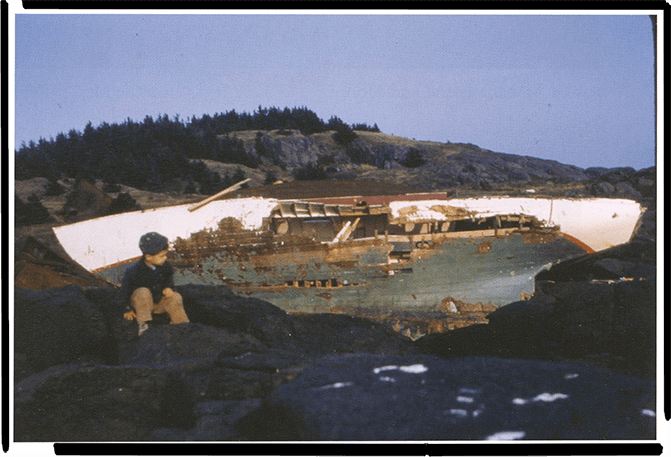

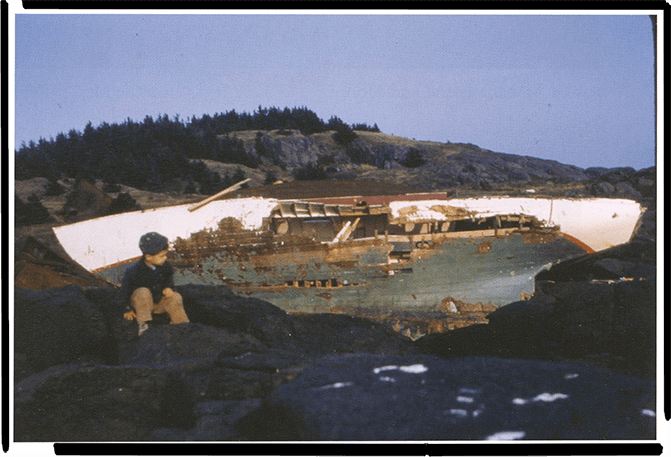

Ernie’s post between Fort Point and Browns Head was at Heron Neck Light on Green’s Island, a “stag” lighthouse which, because of size and conditions, required him to be posted there while his family stayed nearby. It was at Heron Neck that Ernie experienced one day that would eclipse the others for testing his maritime mettle.

Ernie remembers it like it was fifteen minutes ago. “We had a 16-foot unsinkable boat to get mail and so I could go occasionally to see my family at Vinalhaven Island. One day there was a knock on the door and there stood a man with a two-year-old girl under his arm and a five-year-old son next to him. They were all sopping wet because their boat had overturned on the other side of the island.”

The frantic man proceeded to tell Ernie that his fourteen-year-old nephew was stranded on a half-tide rock. Ernie already knew the conditions. The tide was coming in and the waves were three to four feet. The man also informed Ernie that the boy couldn’t swim. And there was one more complication.

“Our unsinkable boat was in for repair,” Ernie explains. “All I had was my own ten foot punt with a five horsepower motor. So I motored out around the island and maneuvered inside the rocks which was difficult with the high surf. I passed him four times but he was too scared to get in. So on the fifth pass I grabbed him by the shirt and got him in the boat.”

If that sounds like a story that should be in a book, it is. Years after he hung up his Bunsen burner, Ernie and Polly collaborated on a book about their lighthouse days. Always a true team, they split the writing. Pick up a copy and on one side you’ll find Ernie’s version, “Lighthouse Keeping.” Flip the book over and you’ll have Polly’s, “Light Housekeeping.”

Along with the great collection of stories and memories, you’ll see plenty of photos, sketches and a painting or two. There would be more of those to come from Ernie – the paintings. Enough to fill an art gallery. Or two.

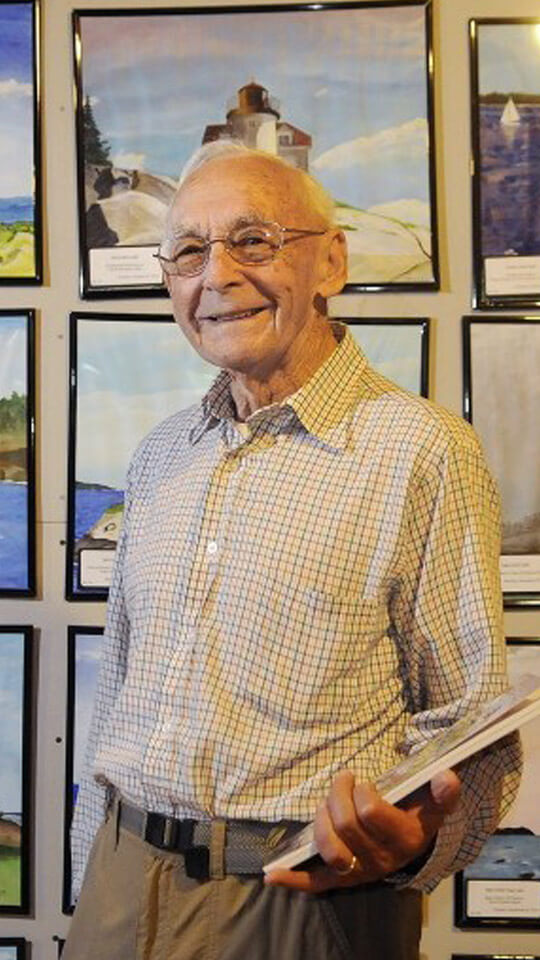

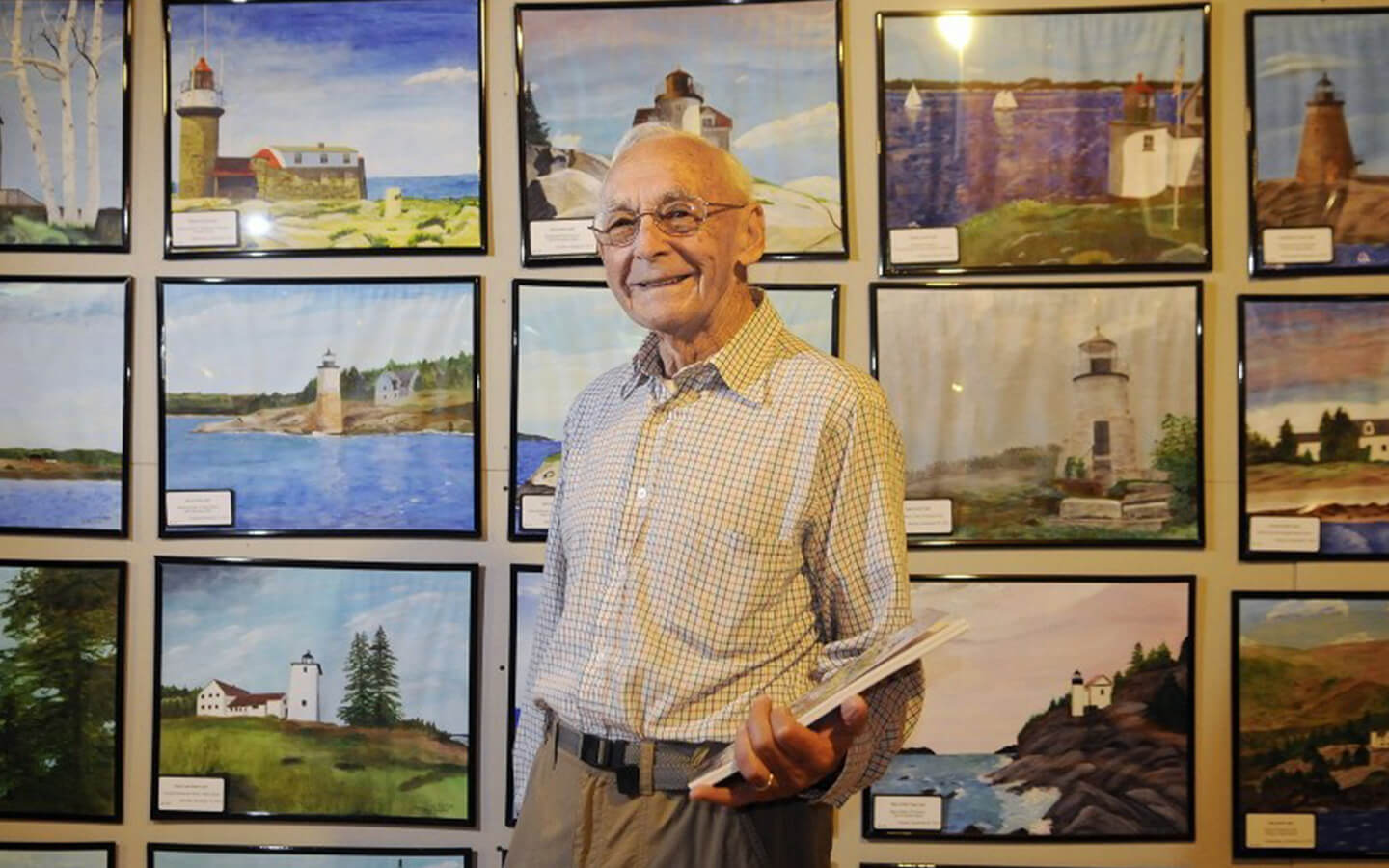

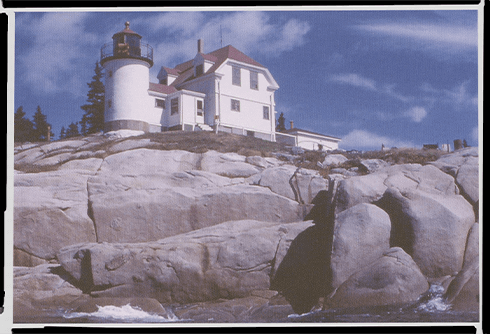

If you flip a Maine state quarter and it comes up tails, you’ll see an image of the lighthouse at Pemaquid Point. It could just as easily have been an image of Ernie DeRaps. You could make an argument that Ernie has done as much as anyone to keep a light shining on Maine’s legendary landmarks. What there’s no question about is that Ernie has painted as many of Maine’s lighthouses as anyone else in the world.

We’re not talking about a fresh coat of exterior paint. We’re talking canvas, palette and brush. How many of Maine’s lighthouses has he painted? It’s an easy answer to remember. All of them. Ernie tells it this way: “When I turned 80, my wife said ‘You’ve been working all these years, supporting the family and all. I think it’s time for you to sit back and do something different.”

Polly reminded Ernie of the more than 3000 color slides he kept in a basement cabinet from his photography experiences. She suggested he could use them as thought-starters for paintings.

“I had always done drawings but never had time to paint,” Ernie says. “So I started painting and decided: ‘I’ve got to do something special here. How am I going to get something different?’ So I decided to paint all 65 of the Maine coast lighthouses. It took me a year and a half to do 65 paintings.”

We’re not sure what the American speed record is for painting an entire state’s-worth of historical icons, but we think Ernie’s safe in claiming it. One thing about Ernie. He’s always been a man with a plan. Before he set sail on his painting odyssey, he curated photos of all 65 of the lighthouses, either taken by himself or, for the locations that weren’t accessible to him, by friends.

Ernie taught himself to paint with acrylics. Beyond that, he’s not terribly concerned with his style or his place in art history books. “I’m not an artist,” he insists. “I’m a painter. I’m a realist. I like to paint them so people know what they’re looking at.”

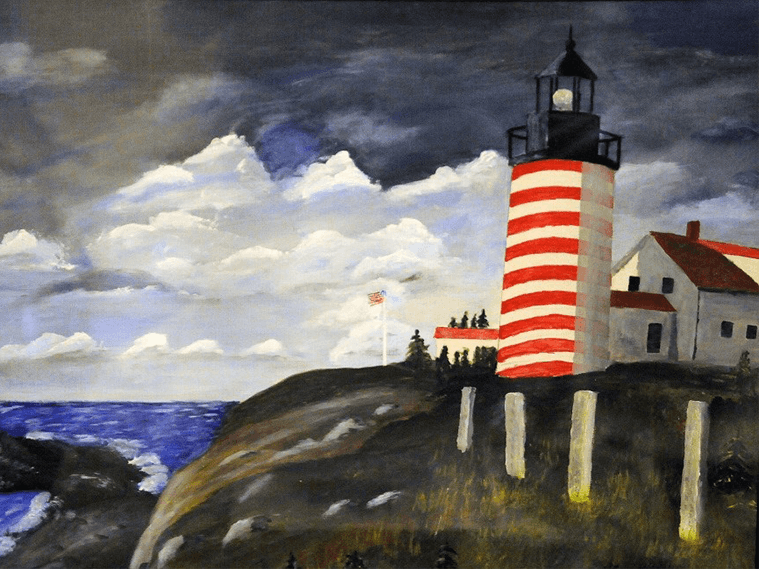

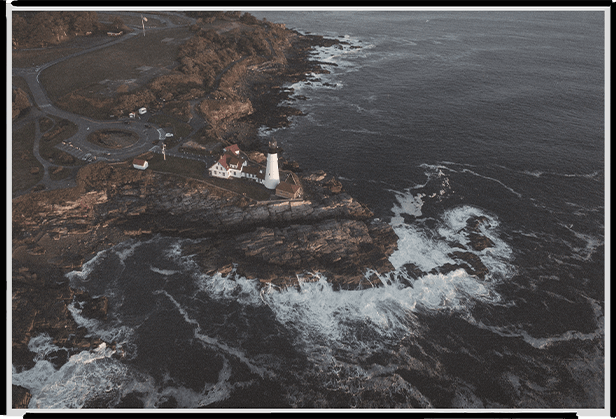

As Ernie knows, each of Maine’s iconic lighthouses earned its iconic status because of its unique, one-of-a-kind structure and a story only it can tell. From the West Quoddy Head light with its candy-striped exterior, to the Marshall Point Lighthouse where Forrest Gump completed the eastern leg of his cross-country run, to the perfectly set and lit Nubble Lighthouse, one of the most painted and photographed lighthouses in the world.

The list goes on and on, straight up to sixty-five. And there’s something more. Since each lighthouse has a uniqueness that can never be duplicated, Ernie makes sure his paintings can’t be either. Whenever he sells a painting, he paints another original to replace it. No reproductions here. Only a return to a time and place and purpose, the likes of which we’ll never see again.

The beauty of Ernie DeRaps' work as painter, writer and ambassador is that everyone from lighthouse aficionados to the lighthouse curious can see these wonders of Maine’s maritime world again and again. In person. Up and down the coast. By land and by sea. As long as there are days that turn into nights.

What is it about lighthouses? What is it that not only captures our attention but fuels our imaginations? Is it what scientists refer to as phototropism – the way living organisms are naturally drawn toward a source of light, modern moths and ancient mariners among them?

There’s probably some of that. But there’s more, oceans more. No one understands better than Ernie DeRaps who puts it this way: “Lighthouses. They kind of grow on you. I wouldn’t have painted them all if I didn’t have a feeling for them.”

A feeling like you have for a friend, someone you can trust, someone who will always be there come hell or high water? Ernie thinks so. It’s that and the vital and often dramatic roles they’ve played in people’s lives on the historic coast of Maine and coastlines throughout the world. That’s what makes it so essential that we remember them and the folks who served from their towers.

“Because it’s history, we tend to forget,” says Ernie. “When the lighthouses were in operation, we’ll never know how many lives or ships were saved.”

There’s poetic justice that after all the years of keeping watch in the past, folks are starting to keep a watchful eye on the future of Maine’s lighthouses. The American Lighthouse Foundation, headquartered in Owl’s Head Maine, in the shadow of the Owl’s Head Lighthouse, is one organization that’s especially enlightened. Some of the individual lighthouses have their own associations that have come together for their preservation and protection.

There’s room for you in the keeper’s quarters too. With every lighthouse or museum visit or boat tour of the lighthouse islands, you can connect with this very special part of Maine’s and America’s history. When we asked, Ernie shared a couple of his favorites – in addition, of course, to the lighthouses he got to know up close and personally.

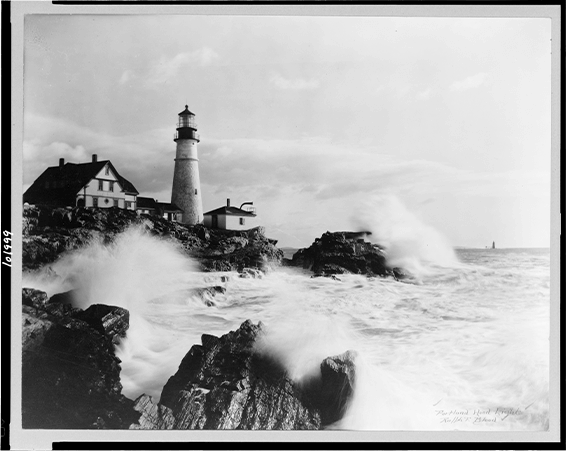

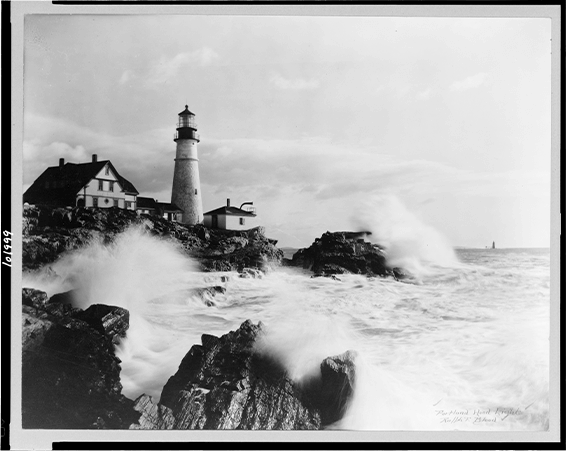

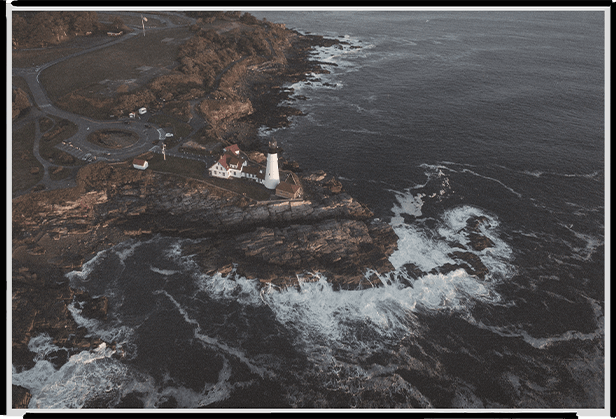

“I would say Portland Head Light,” Ernie suggests. “Pemaquid is very popular. And the Maritime Museum in Bath. You can learn about lighthouses and how they’re taken care of.”

At Pemaquid Point Lighthouse, you’ll even find a couple of Ernie’s paintings. Feel free to buy one. He can always paint more. When you get to Bath and the Maritime Museum, make sure to check out the video of Ernie talking about his lighthouse experiences. It’s called, as it should be, “Into the Light.” And watch for Maine Open Lighthouse Day each year in early September when folks can explore more than 20 of Maine’s historic lighthouses. You might even bump into a special gentleman who’s made a little lighthouse history of his own.

“There aren’t too many of us lighthouse keepers left,” Ernie reflects. “We knew the reason we were there was to help save lives. That’s why lighthouses will always have a special meaning to mariners.”

With Ernie DeRaps shining a light on their storied history, Maine’s lighthouses will continue to have a special meaning for everyone who takes the time to make their acquaintance.